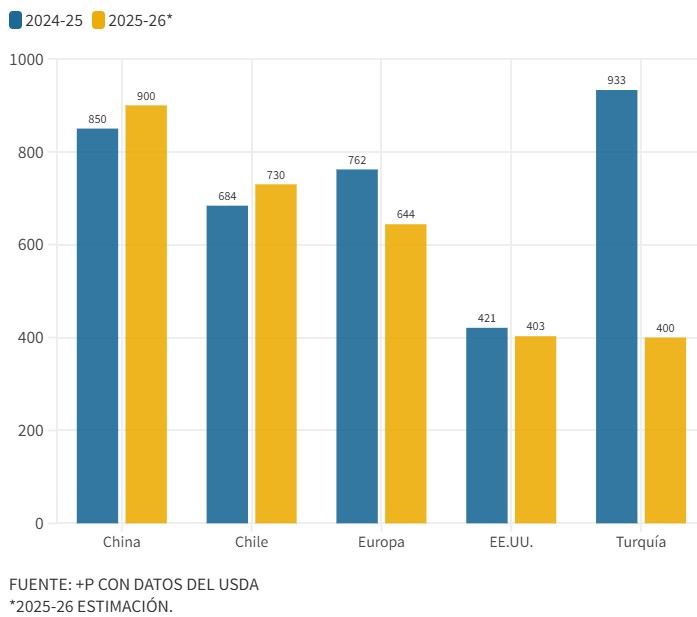

The international fresh cherry market is facing an unexpected turn. The latest report from the US Department of Agriculture (USDA), published in September 2025, projects that global production for the 2025/26 marketing year (MY) will fall by more than 10%, to 4.6 million tons.

This is the first global decline in six years, attributed to severe losses primarily in Turkey, Europe, and the United States.

The USDA emphasizes that it is crucial to note that the 2025/26 MY for fresh cherries covers the period from April 2025 to March 2026, with the Northern Hemisphere’s main marketing season concentrated between May and September 2025.

Globally, although the supply decline is partial and is somewhat offset by increased production in Chile and China, the international market readjustment has an inevitable consequence: higher prices in major high-consumption markets.

This situation has reduced access to cherries in regions traditionally supplied by Turkey and, at the same time, opens economic opportunities for emerging and established exporters.

The Turkish case is key to understanding the current price volatility. With a projected drop of almost 60% in its production—to just 400,000 tons—the country loses a significant portion of its export capacity. According to the USDA, exports will plummet by 85%, to only 10,000 tons.

This adjustment eliminates 56,000 tons from international trade in one fell swoop, a loss that no single supplier can fully compensate for. Turkey, the third-largest exporter in 2024, will drop to eighth place in just one season.

Cherries: Top Global Producers (In thousands of tons)

Rising Prices

The immediate impact has been seen in the price dynamics. During the first three months of the 2025/26 marketing year, Turkish export unit values doubled compared to the previous year. However, the domestic market became even more strained: the shortage pushed domestic prices to record levels, incentivizing producers to direct up to 98% of the harvest to local consumption.

Turkey’s disappearance as a reliable supplier created a void in key markets such as the European Union and Russia, where importers had to seek more expensive and logistically distant alternatives.

In the European Union, production fell by 15% to 644,000 tons due to frost damage in Poland, Greece, and Italy. The bloc became more dependent on imports at a time when its main supplier, Turkey, could not meet demand. The result: a 60% drop in EU imports, which fell to just 23,000 tons. This decline did not reflect a voluntary reduction in consumption, but rather rationing due to high prices and lower availability.

In the United States, the situation is different but also challenging. With production at 403,000 tons—18,000 tons less than in 2024/25—the country had to compensate for its deficit with more imports. Off-season imports are expected to increase by 25% to 30,000 tons, mainly from Chile. It remains to be seen how this will impact domestic prices.

It is worth noting that cherries are a product that is not available in significant quantities year-round. There are two periods when supply is almost nonexistent for the Northern Hemisphere: the months of April and October.

The context of low production in Europe and the United States strongly pushed prices up this season, so it is likely that when cherries from the Southern Hemisphere enter these markets, prices will be at a much higher level than last season. We are always talking about a high-quality product. This is important information for the start of the southern hemisphere season, especially for the exportable supply destined for the US and European markets.

China and Chile: Winners in a Tense Market

In the face of global contraction, China and Chile emerge as the major winners. China, which will reach a production of 900,000 tons, consolidates its position as the world’s largest producer. However, growing domestic demand outstrips supply: its imports will increase by 8%, reaching a record 600,000 tons.

The purchasing power of Chinese consumers, especially in the premium segment, makes the country the main driver of international prices.

Chile, for its part, positions itself as the key exporter in 2025/26. With a record production of 730,000 tons and exports of 670,000—a 10% increase—it becomes the major supplier to compensate for the Turkish crisis during the 2025/26 marketing year. This leading role gives it unprecedented negotiating power in Asia and the United States.

Furthermore, the fact that its season complements that of the Northern Hemisphere allows it to take advantage of high prices—which, as mentioned, are already rising—during the off-season months.

The paradox of this cycle is that, despite the reduction in global production, the worldwide cherry trade will remain stable at around 939,000 tons. This is due entirely to the export boom in Chile. However, this statistical equilibrium masks the reality of prices: less competition and the concentration of supply in the hands of a few players result in a more expensive and more volatile market.

In short, the USDA report indicates that, in economic terms, the Northern Hemisphere behaved as follows:

- European importers faced the largest price increases, since Turkey supplied nearly 75% of their imports.

- Russia suffered less thanks to alternative, low-cost suppliers such as Uzbekistan, Iran, and Azerbaijan, although it will have to pay more for logistics and the diversification of supply sources.

- The United States and China, with greater purchasing power, absorbed the price increase without significant drops in consumption, consolidating the trend toward a polarized market, with high-income consumers on one side and regions that reduce demand due to price on the other.

Outlook and risks

The USDA warns that global consumption of fresh cherries will decline in 2025/26, with significant decreases in Turkey and the European Union. This reduction is due not only to lower availability, but also to the higher price of cherries at retail.

Globally, for producers, the current situation presents expansion opportunities, particularly for Chile and, to a lesser extent, for emerging exporters in Central Asia. However, this concentration of supply also entails risks: any climate shock in Chile, for example, could trigger an even greater surge in international prices.

It will also be interesting to see what strategy Chilean cherry exporters adopt in the Chinese market, where last year they faced negative average profit margins due to oversupply and inconsistent fruit quality during key periods in January.

The projected global decline in cherry production in 2025/26 is not just an agricultural issue, but an economic phenomenon with global repercussions. International prices are already trending upwards, and everything indicates that they will remain high during the arrival of the Southern Hemisphere’s harvest, potentially marking a period of greater volatility in the cherry trade.

While the European Union and Turkey face losses, Chile and China are seizing the opportunity to consolidate their leadership. Ultimately, the end consumer, especially in regions with lower purchasing power, may bear the highest cost: less access to an increasingly exclusive product.

Source: Más Producción