This cherry season, like the last, will undoubtedly be unforgettable for its economic results. During a 17-day visit to the Guangzhou market, we were able to observe the market’s reaction and the condition of the fruit for varieties harvested in December and early January.

This article is not intended to be a chronological or statistical observation, but rather a compilation of impressions, which are grouped into two main areas: fruit quality and condition, and market management and reaction.

Even at the beginning of the packing process for the Lapins variety in Chile, a high incidence of bruising from the harvest was observed. In the destination market, this damage translated into significant quality differences between companies. In some boxes, the bruising was evident on the top and sides when the bags were lifted.

The condition of the pedicels was another parameter that caught our attention. Although they weren’t brown, they appeared tired and thin. This was compounded by the fact that the fruit was packaged in dark mahogany colors with a dull appearance, resulting in a poor overall presentation of the boxes.

Another significant problem observed both during processing and upon arrival was splitting. The condition of the pedicels could be related to the reduction in hydrocooler exposure times, a practice often implemented to decrease the incidence of this damage. While it’s true that overexposure to water can cause splitting, it’s a consequence of prior handling and climatic conditions.

As with other symptoms, this is a hidden problem that the hydrocooler eventually reveals. Reducing the time isn’t wrong, but it’s crucial to ensure that the cooling is effective and that all the fruit is properly moistened.

In some cases, the incidence of splitting was high at the source, leading to the packaging of fruit with this defect, always within the limits permitted by the standard. However, this damage increased due to recurring drizzle and high humidity throughout the season. As with bruising, variable results were observed among companies at the destination regarding the removal of these defects.

The cracks were often packed, but we also observed some developing fresh during transit. This damage primarily affected the Skeena variety, causing it to lag behind in sales and delaying its arrival on the market by several days.

In some cases, labels with cleanliness issues were also observed, evidenced by the presence of Alternaria at the base of the fruit or associated with pre-harvest wounds. The main problem was that, during transit, the fungal growth in cracks, bruises, and spots resulted in Alternaria colonization or mold development.

A smaller percentage of labels also showed signs of yeast-induced rot. Although the volume of affected fruit was low, the severity of the infestation was striking.

To avoid focusing solely on the negative aspects, it’s important to highlight the good work done in terms of size and firmness, as the vast majority of the fruit showed positive results in these areas. Label segregation is also generally adequate in the industry; however, the packaging of dark fruit on secondary labels needs to be reconsidered.

Most companies perform very good color separation, but the classification between light and dark fruit needs to be better organized, as in some cases the latter appears excessively light.

Flavor is an aspect that will require more persistent work. Despite having good °Brix levels, the fruit was perceived as having a flat flavor, which was not well received by buyers, who complained of a loss of flavor and, in some cases, mistook this for bitterness.

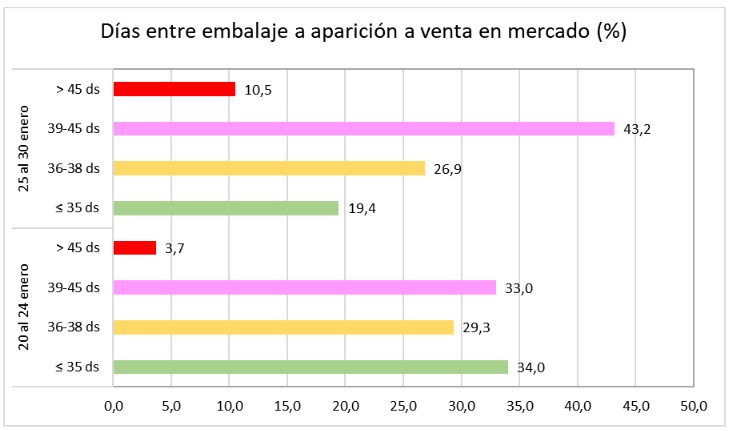

Up to this point, the quality and condition of the fruit upon arrival at the market, corresponding to a period of 29 to 35 days after the packing date, has been characterized. However, this season saw some unique conditions, including earlier harvests and a lower, though still high, total volume than the previous season. This was compounded by low prices, which delayed the marketing process. Consequently, the fruit reached the market older, potentially affecting its condition and final quality. (Figure 1).

With this increased age, and under varying temperature conditions, product deterioration began to be observed. Rot became more visible in fruit that had not been removed during cleaning; cracks began to be colonized by pathogens; spots and bruises became covered in mold; and when the temperature fluctuated significantly, slightly spicy flavors appeared, resulting from gas alterations in the modified atmosphere bags. In the Regina variety, browning, which was already slightly visible at 35 days, increased in both quantity and severity.

However, not all the fruit deteriorated during this period. In cases where proper cleaning was performed and the cold chain was adequately maintained, the product appeared aesthetically pleasing and even had good pulp quality. Nevertheless, the lack of flavor again became a critical factor, leading buyers to complain about changes in the fruit’s sensory profile.

This is an aspect that must be explicitly incorporated into post-harvest evaluation. Flavor, a concept much broader than sugar content, must be carefully managed to maintain its quality for up to 35 days, thus offering a pleasant consumer experience and encouraging repeat purchases.

This has been a challenging season that compels us to reflect on how to face the future. There are many areas for improvement, but undoubtedly, quality, understood as a holistic concept, along with the product’s condition, constitutes the first pillar on which we must focus our efforts.